We are born to be storytellers and whether that’s a curse or not is for you to decide. We’re dropped onto the surface of the Earth by storks (science) and then given a brain that is imperfect, overthinks or thinks not at all, doubles down on some facts and experiences and forgets others entirely. With this imperfect brain we then spend our lives forming and reforming narratives to explain ourselves. We connect the dots as best we can, continuously sifting through (or stuffing down) the evidence we have at hand.

Just like feelings aren’t facts, our stories aren’t either. A story doesn’t need to be epic or complex to still be a story. A story can be “No one will ever love me” or “My sister thinks I’m an idiot.” We think stories have to be long, or even have to be books, to be important, but we’re all telling ourselves stories every single day of our lives. We’re either anxious or excited about something (similar physical sensations, different mental framing). We’re either staunchly independent and capable because of our parents’ benign neglect or we’re stunted and overly dependent on others for validation (same foundational story, polar opposite takeaways).

The thing is, there is no one objective truth about our lives or anyone else’s life for that matter. We can only see our lives from the inside, knowing everything, or so we think. Or at least we know the backstory, we have that part down pat, we tell ourselves. But do we?

Everyone else sees us from the outside—knowing either nothing at all or quite a bit actually (they think). The people in our lives might think they’re objective about us, but of course that isn’t even remotely true either. They are not us. We are not them. And there really is no magical place where every possible internal and external version of ourselves, every emotional script, every experience, all the facts and figures, and everyone’s various perspectives of knowing us all dovetail neatly into The One Singular Truth.

When I was writing my two memoirs(-in-essays), I always felt the pull of wanting to tell that One Singular Truth, long before I realized that it’s impossible. As I hit on sudden insights or felt a narrative suddenly click neatly into place it felt pure, like a high. Had I finally figured myself out? How could this not be The Truth if it made so much sense? If it felt like it healed some part of me? If it made me want to dig even deeper, to understand even more? It’s a powerful, and somewhat addictive, experience to feel like you’ve figured yourself out, all on your own. It’s why some of us can’t quit memoir.

But I got things wrong in my own writing about my own life. Some factual and some perceptual. There is also the reality of omission. Ask any woman who’s written a divorce book (and I have connected with many of them) and whatever you think you know there is, of course, so much more that you will never know. First of all, no one likes being sued. And consciously or not, everyone is shaping their narrative, revealing as little or as much as they want you to see and how they want you to see it.

It’s surprising, then, that as a reader I forget absolutely all of this. I gobble it all up, take every word as gospel. I assume I’m reading the expansive truth.

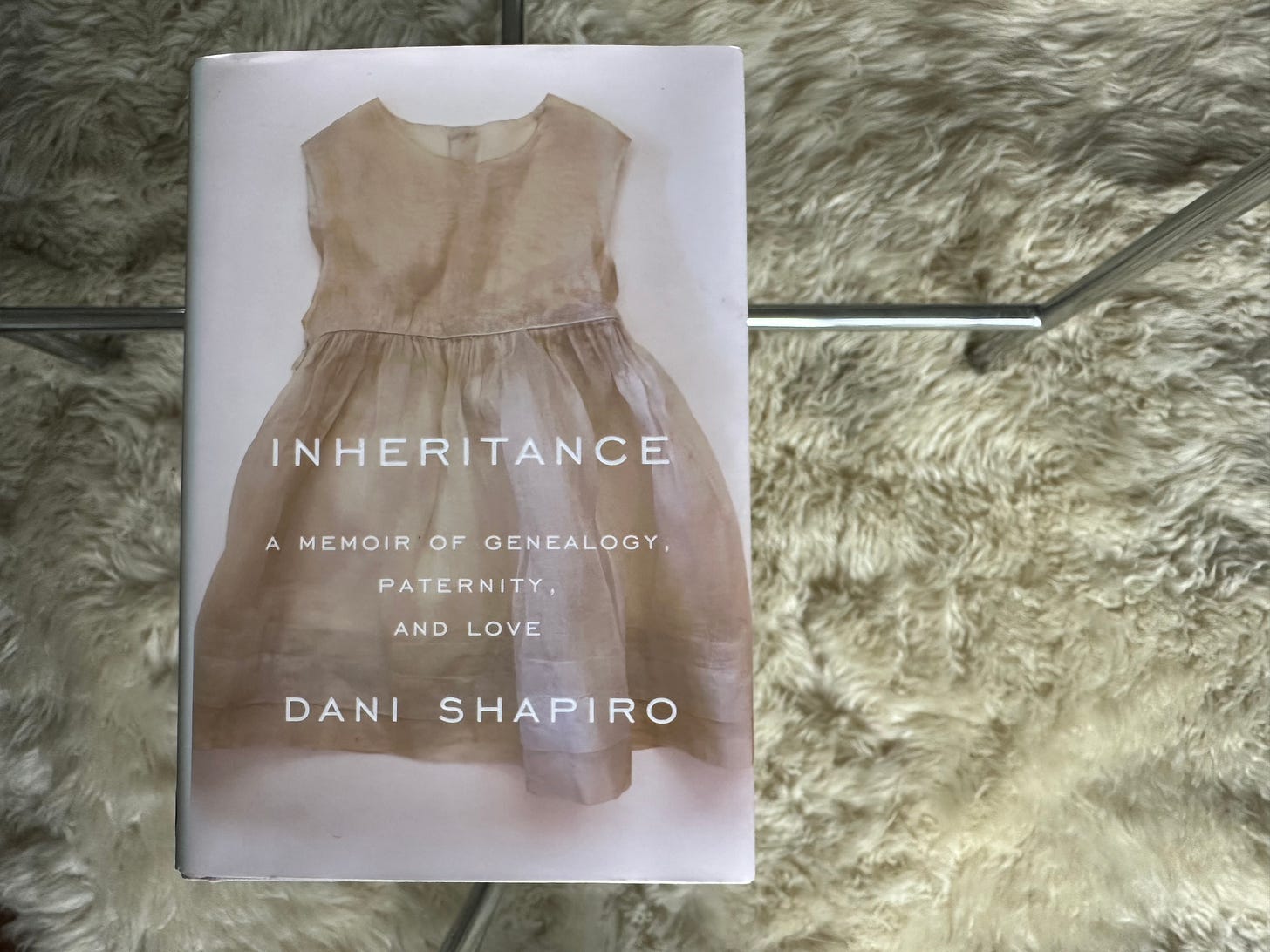

Over the past year this theme has come up repeatedly in my reading. I started thinking about this while reading INHERITANCE: A MEMOIR OF GENEALOGY, PATERNITY, AND LOVE by Dani Shapiro. It’s a tremendous book. From the jacket copy (not a spoiler):

In the spring of 2016, through a genealogy website to which she had whimsically submitted her DNA, Dani Shapiro received the astonishing news that her beloved deceased father was not her biological father. Over the course of a single day, her entire history—the life she had lived—crumbled beneath her.

Quite far into the book, there was this:

“I grew up to become a storyteller. I moved from fiction to memoir, writing one, two, three, four—now five—memoirs. I captured my life, and the life of my family, between the pages of book after book and thought: There, that’s it. Now I understand.”

“There, that’s it. Now I understand.” I can’t imagine describing the point of memoir any better or making its meaning for the author any clearer.

Right after I finished that book, I came across “Last night an ENT saved my life” by

that opened with this:I’ve struggled with a battery of sleep issues since I was a young girl. If you’ve read my memoir THE YEAR OF THE HORSES, you’ll know that I equated the onset of my sleeping problems with the unraveling of my parents’ marriage and my younger brother’s heart issues, all of which intensified when I was eight. Well, I might have to put out an edited version of that memoir because yesterday I received a diagnosis from an Ear, Nose, and Throat doctor that might change my life.

The full piece is worth a read, as an example of how we use the evidence at hand to draw conclusions about our lives. In medicine and criminal investigations the simple explanation is often the best one. Why would memoir, of all things, be any different?

This piece also shows that especially for women, so much of what we wonder or worry about when it comes to our lives and the challenges or trauma we feel, is thrown back on us (either by others or ourselves) as all our fault, all in our head, all because of overthinking, all because we just can’t chill the fuck out.

My final example of this is more recent. The other day my mind wandered back to the days when I was constantly on Twitter. As nostalgia tends to go, I was remembering mostly the good stuff. I thought about all of the authors I got to know (or at least follow) before I had actual authors in my actual life.

I remember following

Taylor who I thought was a comedy writer at first. I remember that loves peonies because he would ask his followers to tweet him peony photos every spring (and I did). And I connected with loads of women writers in general and comedy writers of all stripes near and far, of all imaginable levels and experience, and some of them became my real life friends.Then I thought of tragedy, too. I’d think of the times something horrible happened and it’d be shared out into the ether in real time. I thought about when Molly Brodak died from suicide and her husband tweeted that news. And I thought about all the reactions, comments, and retweets that populated my feed because of it. I didn’t know her or her work, nor did I know her husband nor his work either. But I remembered that moment. Then I tried to remember how long ago that was and what was his name again?

That’s how I found MOLLY by Blake Butler. Once I found the book I also found a churning discourse about truth, who is allowed to write what about whom, and which evidence you should or shouldn’t be allowed to employ in shaping that narrative.

I immediately found “Who Gets to Name What’s Evil? On Blake Butler’s ‘Molly’” by Mike Jeffrey in the Los Angeles Review of Books. In just skimming the review I thought yikes and decided I didn’t want anything to do with that book. Then only a few weeks later I thought about the book again and was like, fuck it. And bought it.

I braced myself for the book to be terrible and for the fact that I had bought a terrible book on purpose knowing it was terrible. But that wasn’t my experience of MOLLY at all. Sometimes I wonder if I don’t know how to read correctly or if my brain is broken. Like do I know what a good book is? Or a bad one? When I see lots of people praising a particular book when I think that book is an absolute pile of shit it does makes me wonder. And when the fancy people say a book is terrible but I like it, what does that say about me?

As I got further into MOLLY, finding it compelling, I checked Goodreads which is like checking WebMD for symptoms. If you’re checking either of these sites for objective non-alarmist insights you’re already dead. The first review gave MOLLY five stars and provided a thoughtful and detailed review of the book. Right below that was a two-star rating and a review that read in full: “A long winded ‘am I the asshole’ Reddit post.” LOL.

Goodreads aside, I suspect that this is a literary warfare situation, writer versus writer, except one of the writers is dead and the subject of an entire book. So instead it’s different literary and personal camps going at each other, women versus men, some-things-should-always-be-private versus use-all-the-evidence-at-your-disposal-to-make-sense-of-what-the-fuck-just-happened philosophies. It’s also a debate about how far we go in sharing anything about our lives and especially the lives of others who certainly didn’t ask to be written about or no longer have a say in the matter. Is that exploitation or is that seeking some kind of truth? Is it both? For all these reasons and questions, I’m glad I waited until I was done with the book to read other reviews.

Writing about someone—another writer, no less—after they’re dead, even if they were your wife, certainly guarantees that what you create is a type of truth. While Butler draws from his life with Molly and from publicly available sources like her books and poetry, he also shares her suicide note and, later, deeply personal information from her journals and her phone. Is that truth? Or is that no one’s fucking business? I remain conflicted. But I loved the book. I read it in 30- or 40-page chunks at a time, perhaps entranced by how the author attempts to make sense of something that he will never have answers to. Not only is landing on the “real” truth impossible generally speaking, once someone is dead they take every deeper insight and detail to the grave with them.

Patricia Lockwood also weighed in on MOLLY in the London Review of Books (“The Secret Life”). Of course even if Molly was alive and wrote this book herself, we still wouldn’t know The Truth. Setting aside for the moment that the inciting incident for this book, her death, makes this mental exercise nonsensical, she certainly wouldn’t have shared her affairs, her journal entries, her sexting—or would she? She wouldn’t see herself as difficult, abusive, a terrible partner—or would she? And, most importantly, was she actually any of those things? Did she actually do or say any of those things? We will never know. And is it anyone’s business? Well, art is a business. So there is that. And there is just the one story, written by this one person. Perhaps that’s why this stood out to me from the above review:

“I felt Molly in this book, but a different one: the small allotment of her that I had. The people who surrounded Molly share something, maybe – a hesitance to claim her. If we called ourselves her friends, would she reject that? She sent a few people cookies on the day she died. It was the great uncrossed-out thing; it was what she could do. She might roll her eyes at us; so what? Maybe in the end it is better to make the claim. I knew Molly; I walked with her a little ways.”

Maybe when all is said and done (and written), it is better for writers to make the claim. To say we knew ourselves, or at least that we walked with ourselves a little ways.

FURTHER READING

• “Can a Memoir Say Too Much?” by Alexandra Schwartz in The New Yorker

You can find my books here.

You can find more writing here.

You can find my work for brands here.

You can find me wasting time on Instagram.