"How do you/how can I have a successful writing career?"

My book advances, my day rate, and what qualifies as "successful"

Now THAT is a question. The question of all questions. I want to say that it’s the million dollar question but in this economy? I don’t think so. It’s also a question that assumes I’m actually successful. We’ll see about that, won’t we?

Pay transparency is building momentum across industries. I agree with it in theory and am terrified of it in practice. I was taught long ago that it’s not polite to talk about money, just like it’s not polite to talk about death or sex. But not talking about difficult things helps no one. And ultimately, the concept of pay transparency (or lack thereof) is an opportunity to reflect on who it really serves when we don't disclose our salaries, advances, and/or day rates. (sidebar: if you take a look at my advances and day rate and think this bitch is grossly underpaid, please contact me immediately.)

And I think it’s pointless to have a general conversation about how to have a “successful writing career” if we aren’t straightforwardly including money in that conversation. And, related, getting really clear on what “success” even means. Signing with an agent, signing a book contract, going on a (probably unpaid) book tour, yes, they all look great. They make for very good content. But what does any of it really mean? Rubber, meet road. And let’s get transparent, shall we?

Publishing

If you’ve read this newsletter or followed me for a while, you’re probably familiar enough with how I became an author so I don’t want to belabor it here. But the tl;dr version is I started focusing on my own writing in 2015, had an agent approach me in 2016 (and I signed with him), got my first book deal in 2017, and my second in 2019. Yes, it all happened fast. This nutshell-like recap makes it sound like I sprung fully-formed from a pod as a writer in 2015. But at that point I had been working and writing in creative fields since I was in college (24ish years?). But still, all things considered, I had it easy. But does that mean I’m successful?

You tell me.

Before we get to my numbers, below is one of the best explainers I’ve seen on book deals. It’s easy to follow and easy to understand or at least as easy as it will ever be to understand book deals and money. It should also make clear why publishing: a) makes no sense, b) no one understands it, and c) precious few writers actually make a living from writing in general and even fewer make their living from writing books exclusively: “An Agent Explains the Ins and Outs of Book Deals” by Kate McKean (who also writes a truly excellent newsletter here on Substack, Agents + Books)

Let’s get to my numbers:

• My advance for AMATEUR HOUR was $40,000. I was shocked, actually, as my agent told me to expect less. And because all of this was new to me, I was just beside-myself thrilled to get an advance and sell a book at all. If you read the above article, though, you’ll know that while that is a fairly decent chunk of change, it was paid out over about a year (it was a fast book and yes that’s considered fast in publishing), my agent took 15% off the top, and of course I had to pay taxes on it as well.

• One completely maddening thing about publishing (of which there are many) is that there’s no way for authors to see how many of their books have sold with any sort of up-to-date accuracy. Like, what other industry is like this with product? None? And yes BOOKS ARE A PRODUCT. Anyway, last I knew AH sold about 12,000+ copies. That’s a lot of books! But it isn’t even close to earning out. Not. Even. Close. Earning out = starting to earn royalties (more money) on your book.

• My advance for BUT YOU SEEMED SO HAPPY was also $40,000. This was paid out over an even longer stretch of time (two years) since I had more time to write that book. And again, my agent took 15% off the top. And taxes. Annnnnd, punch line:

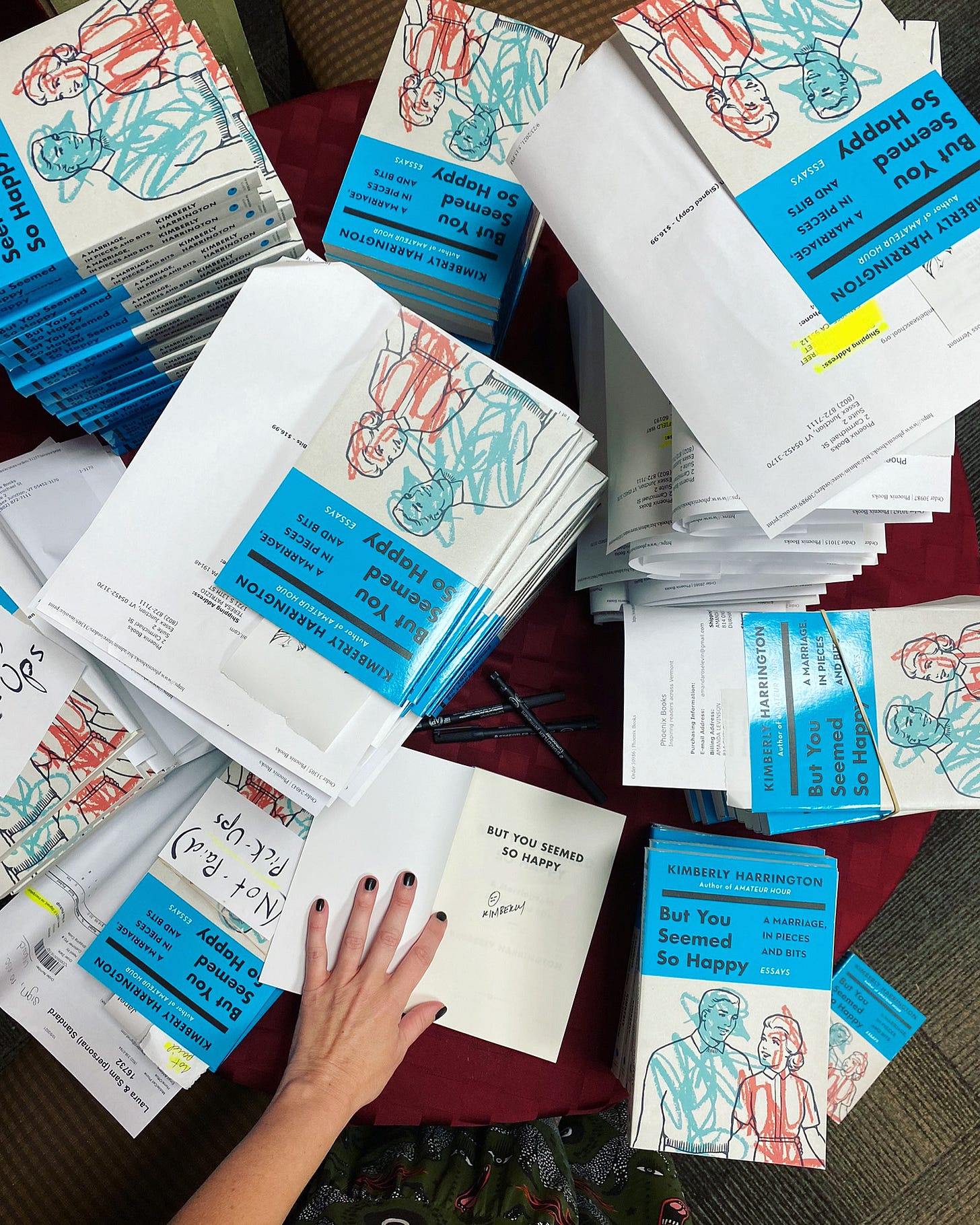

• BYSSH tanked in sales. I’m not sure what the current sales figures are but last I knew it hadn’t even sold 4000 copies. While that’s still a whole bunch of books, it’s nowhere near what AH sold and although my editor diplomatically told me it wasn’t “a career ender” I wouldn’t say that’s exactly encouraging lol.

• To be crystal clear, I’m not continuing to make money off of these books! The advances were it. If you buy my books now that’s great! But that money goes to my publisher, to continue chipping away at the advances they’ve already paid me. Advances do not need to be paid back (thank god) but I also don’t earn any more money on either of my books until sales exceed the amount of my advances.

• Maybe you’re thinking but what about all your bylines? Nothing I’ve ever written specifically for any mainstream publication has ever cracked $1k and most haven’t cracked $600. Book excerpts might have, but that money went directly to my publisher (again, to pay down my advances). I haven’t submitted any humor in a year but last I knew The New Yorker pays $350 for online and much more for print ($2k I believe, I’ve never made it into the print magazine). McSweeney’s pays $30. So much for supplementing book money with this money! ☹

Last year, Mandy Len Catron wrote about her foray into the #PublishingPaidMe swirl, where she shared that she had earned a $400k advance (I choke, I sob, I die a little inside) for her book based on her mega-viral Modern Love essay. The point of #PublishingPaidMe wasn’t for authors to brag — far from it — but instead to make visible the stark racial pay disparities in publishing. For example, it’s well-known that Roxane Gay received only a $15k advance for BAD FEMINIST.

Publishing is built on the murkiest least accessible data, and it’s that lack of data that stokes the insanity of every author and every want-to-be author. It deepens and encourages a culture of inequality. I deeply appreciate MLC taking the leap on Twitter and again in describing the blowback. And also relating her firsthand experience of understanding that a good book doesn’t necessarily mean a successful book. And we all know that plenty of truly terrible books go on to be bestsellers. Anyway, I encourage you to give her post a read: “Let’s talk about money, baby”.

An excerpt:

“In the literary world no one talks about money, though every writer I know is obsessed with it. Or every writer I know is obsessed with the thing money can buy: time to write. Publishing can be a brutal industry. But then any creative life is a poor fit for capitalism. In our culture writing is both a passion that you should pursue for little or no pay and it is a career where the only legitimate version of success is the one where you make a living from your art. Because we want both things to be true, most of us never acknowledge how money comes to bear on our writing lives. Instead, we’re all scrolling through Instagram sure that everyone else resolved this contradiction years ago and wondering where we went wrong.”

So am I a publishing success? What do you think? This is where the definition of “success” comes into play. If you gauge success by books sold and financial reward and/or stability then, no, I am definitely not a success. I mean, it kind of seems like I’m a failure by any sane measurement, right? But publishing is not sane.

If you gauge success by having two books published by a Big 5 publisher — the first the year I turned 50 — then hell yes, that feels like a major success! People are always impressed that I’ve written two books. I mean, I’m impressed that I’ve written two books. The fact that I’m a published author helps bring other work in the door. I read somewhere, in the lead-up to launching my first book, something along the lines of “you’ll always be able to say you’re a published author and no one can ever take that away from you” and it’s true. There is not a small amount of pride in that.

If you gauge success by getting good reviews and book excerpts placed in plum publications then I’m a fair success on one book and a middling failure on the other (ha). And if you gauge success by having actual readers who’ve read your actual books reach out to you and tell you that those books meant something to them, and that they also went on to share or buy your books for people who mean something to them too, then I’m a resounding success.

But, obviously, none of the above equals financial success, or anywhere close to the level of I-only-write-what-I-want-to-write success. So: how do I have a successful career in publishing? I don’t! How can you? Beats me! I’m sorry, I wish I had better answers. Maybe try being a royal, a very consistent Socialist grouch, a famous actor or actress, a former First Lady, or a fascist first? (Don’t be that last thing, it’s not worth the book sales).

Further reading:

• “Where is all the book data?” by Melanie Walsh. “I went looking for book sales data, only to find that most of it is proprietary and purposefully locked away. What I learned was that the single most influential data in the publishing industry—which, every day, determines book contracts and authors’ lives—is basically inaccessible to anyone beyond the industry.”

• “No, Most Books Don't Sell Only a Dozen Copies” by Lincoln Michel* (*Be sure to read the comments on this one, especially the top one from Kristen McLean, lead industry analyst from NPD BookScan. “I think the real story is that roughly 66% of [the] books from the top 10 publishers sold less than 1,000 copies over 52 weeks.” 💀 Ok, maybe I AM a success after all.

• The only good pre-order newsletter/email/request in existence! “i wrote another book: please buy it or i will die” by Sam Irby.

Advertising

I’ve written before about my strange and winding career in brand, advertising, and design. And you might even be able to Google an article here and there about my spicy opinions on it. But my main point for this particular newsletter is this — I always wanted to work in advertising. And my main response (in my head) to most people asking me how to be a successful copywriter is — and I’m not sure you do.

I interned at DDB Needham in LA while I was still in college and it’s where I landed my first official job in advertising. It was so long ago that I regularly wore skirts, hosiery, jackets with big shoulder pads, and pumps to work. As an assistant. I went on to work at Wieden+Kennedy during the nineties and if there was anywhere to work in the nineties it was there. I thrived on the chaos and built-in social life. I loved, loved, loved learning about how the work happened. I could not have been less prepared by my upbringing or my parents’ occupations or anything I knew to that point for this profession. I was a Fine Arts major at UCLA but I knew I wanted to do something creative and I knew I didn’t want to starve while doing it.

But even more than the learning and the fun and the strippers and the sex in the bathroom at parties (not me) and the hookups and, oh right, the work, W+K provided a seriously heavy-hitting professional network that sends work my way to this very day. Yes, almost thirty years later.

I didn’t go into advertising as a way to fill the gaps in my income or to support my personal writing. I did it because I was interested in the industry, I wanted to be able to swear freely at work (I’m not joking), I wanted to work with creative people even if I wasn’t one (yet), and I wanted to work in a non-corporate non-tight-ass environment. Was it stressful? Yes. Did I burn out multiple times no matter where I worked? Yes. Did I cry in the bathroom so many times? Also yes. But I learned so much about so much and I was interested in pretty much all of it. I made lifelong friends, met my (ex-)husband, and it set me on a path that has fed me literally and creatively to this day.

None of it was easy. And I was never well-compensated until I was. And by that I mean when I went out on my own as a freelancer in 2009, after being laid off. So when I’m asked how to be a successful copywriter or a copywriter like the kind of copywriter I am I don’t even know how to respond. My path was inordinately twisty and nonsensical. I regularly made choices that made me less money instead of more. Long-term I think they paid off, in learning how to be a better and less asshole-ish creative. But the professional worlds I learned in and the industries that were a part of that landscape have either completely changed or don’t even exist anymore. It’s shocking, actually, how much has changed over the course of my career.

Let’s get to my numbers:

• My last full-time salary was around $80k a year and that was 14 years ago. I haven’t had a full-time job since.

• When I was laid off in 2009 and started freelancing my day rate was $1000.

• Around 2010 or 2011 I upped it to $1500/day after several former coworkers remarked “a bit low, isn’t it?”

• My day rate has been $1500 ever since. Other than the past 3-1/2 year stretch, I have rarely worked on long-term projects where the money could just pile up and up and up. I have feasted. And I have famined.

• When I look back over the past 14 years of freelancing, I’ve had as much as a $75k difference from one year’s income to the next. I wouldn’t say any of this lends itself to stability.

To be clear, I know it is not a small amount of money. I feel extraordinarily fortunate to be working at the level I do and to have my career continue to grow the older I get. And you can imagine that while $40k seems like a fairly decent advance for a book, I could also make that working not-completely-full-time at my day rate for a couple of months. But advertising isn’t a book and a book isn’t advertising. I get that, of course. These are different things with different perceptions and different places of prominence in culture.

This might lead you to believe I am rich or at least financially stable by this point and let me tell you something, I’m neither of those things. I should be. Or I could’ve been. But I’m just not. I’m an idiot is what I am. My network is littered with millionaires and founders, chief creative officers and runners of brands. And I am … I don’t even know what I am exactly.

But am I a successful copywriter and creative director? I don’t have an assistant or a big title or a clear career trajectory. I didn’t win any awards for my work until I was in my fifties, primarily because either I was working at design studios who thought awards were bullshit (they are) or I was freelancing and rarely got work produced. The work I did win awards for, as part of larger creative teams of course, is this and this. So. I guess I consider myself creatively successful if not industry successful. I’m a strong conceptual thinker, a flexible and fast writer with a huge range of ability, an excellent voice absorber, a strong editor, and a good teacher given the opportunity.

Do I wish I was a millionaire? Obviously. Do I regret staying in Vermont and having greater work, parenting, and life flexibility thanks to (extremely uneven) freelancing? Not even a little bit.

I know some people reach out to me because they consider writing their calling but, ewww, not copywriting. They’re willing to do it but want to do it the way I’m doing it (I guess? Who knows.) They need to make money and are willing to lower themselves to what I’ve done for my actual career. Thanks? All I’ll say is if you approach doing a job and give off vibes like the industry, the work, and the people are beneath you then I suggest you find something else to do. I’m not saying (some) advertising is art but I’m not saying it isn’t. And I’m not saying publishing is a business but, oh wait, yes I am. There is no pure calling, I guess is my point. Or, if there is, it’s probably keeping your writing to yourself, to never sully it with commercialism or risk hearing other people’s opinions about it. Let me be clear — there is absolutely nothing wrong with doing just that.

But this newsletter isn’t about the purity of writing, it’s about having a successful career as a writer. And this is the conclusion I’ve come to: I’m not a successful writer, at least in the way our culture defines success — financial freedom AKA fuck-you money. I’m a very good writer in my industry. And I’m a very promising writer in others. I’ve created some work I love and am incredibly proud of. I’ve also created work that is pure shit (this is the journey). I’ve financially provided for my family every. single. year. that we’ve been a family and that is huge. And hard. And it keeps me from doing much more of the writing I would like to do. But I will do more. In many ways, I’m just getting started. Soon I’ll be taking new paths both creatively and for work. And if and when I consider myself thoroughly and completely successful, I promise to let you know how I got there.

Further reading and listening:

• Before Jenn Romolini was the co-host of Everything is Fine podcast, she was a guest on EIF! I remember listening to her interview “The Only Career Advice You Need” and thinking “this is the only time I’ve heard someone else describe what I’ve been doing all along” which was — not caring about titles or having a “big job”, elevating learning over ladder climbing, emphasizing flexibility to live your life (and be available to your family), not thinking your career is over at 40 or 50, and in general not giving a shit what other people think about your work trajectory, position, or path. Give it a listen!

• For those feeling worn down by layoffs, job searches, and/or life in general: “If not Joy, then Joy’s Direction” by Harper Jones. “There are no true objective measures for a bad time, but I was at a moment when I was getting hammered by life: I had been laid off from two jobs in a row — both of which had cost me my house, in the midst of a painful and acrimonious divorce … the idea of what it meant to be a husband and a parent utterly wrecked and with no path to reconstitution. I was in joyless survival mode, and felt the days passing as I dove into one unhealthy coping mechanism after the other (Bushmills, food like a smothering blanket, a droning emptiness in front of re-run movies as my inbox metastasized). On some days some kinds of energy appeared and faded, but it was hard to know what to do — it became another reason to be angry, another cue for despair. So I wrote a little thing that helped.”

• “I understand from having seen 20,000 Days on Earth that you keep an office separate for your creative work. Do you have any recommendations on how I can create a sacred space that allows me to go in and shut the door and lock out the world?” The answer from Nick Cave.

You can find my books here. You can find my writing here. You can find my copywriting and creative direction work here. You can find me on Instagram. Please do not find me in real life, I’m busy scheming and planning and writing my little emails and Word docs.

This is incredibly generous and helpful. Thank you!

Thank you so much for this. I think we all would do better talking about money, especially women, especially creative women, especially creative mid-career women.